Keeping Egg Freezing in Perspective

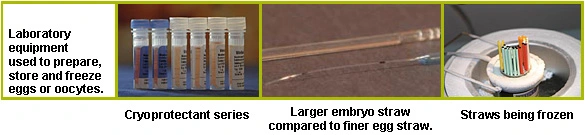

We have learned much about the freezing of human oocytes over the years, yet despite a massive and consistent effort by the scientific community, a reliable method to freeze eggs with the same success as embryos and sperm remains elusive. Our ability to freeze any cell depends on many factors, but most significantly on how much water the cell contains. Because water expands in volume as it turns to ice, cells must be dehydrated prior to freezing to prevent the cell from rupturing. The addition of a cryoprotectant, which does not expand upon freezing, can greatly reduce the risk of cell rupture.

Scientists have been freezing and thawing sperm with good success for over 100 years. In many ways, sperm are ideal for freezing as they exist as individual cells, they are the smallest human cells and they contain very little water. It is thought that sperm can be stored perhaps indefinitely after being added to a solution of cryoprotectant, and then frozen to minus 1960C. In contrast to the sperm, the oocyte is the largest human cell and it contains much more water. The oocyte is also much more sensitive and is very intolerant of the chemical and physical stresses that are created during freezing and thawing.

Further, the availability of oocytes is much more limited. When an oocyte is ovulated, or retrieved from the ovary during an IVF cycle, ideally it is ready to be fertilized by a single sperm. In anticipation of fertilization, the oocyte prepares to discard half of its DNA - a process called meiosis. Any changes in the physical or chemical environment around the oocyte can disrupt meiosis, leading to an oocyte with too much or too little DNA. Even after we overcome the hurdles of sensitivity and cell water content, there are other obstacles to freezing and thawing oocytes successfully.

In scientific literature, most papers that report success with egg freezing involve very few patients and therefore even fewer pregnancies and deliveries. Porcu et al., 1997, Tucker et al., 1998 and Young et al., 1998 are typical examples of papers that report successful deliveries from just one patient's frozen oocytes. Between them, these authors froze 34 eggs, of which 15 survived thawing. In larger studies, Porcu et al., 2000 and Fabbri et al., 2001 were able to obtain large numbers of oocytes for freezing (1502 and 1769 respectively), resulting in overall survival after freezing at just over 50% for both studies. Just over half of the oocytes that survived freezing fertilized, and about half of these made good quality embryos. Yet the number of babies delivered reported by Porcu was low (9 births plus 7 ongoing pregnancies). Fabbri reported only fertilization and embryo development rates as a measure of success in his study and has not yet reported on pregnancies and births.

Wider application and success with oocyte freezing depends on continued improvements with the technology and on careful selection of oocytes to freeze. While many researchers are continuing to improve the freezing process, much of the success so far has been with the use of good quality or young oocytes. In the Porcu study, most of the oocytes were collected from young women who would presumably have good quality oocytes. We would expect results to be worse if the eggs were from older women, although no such studies have been undertaken.

Despite all the hype, oocyte freezing will fall short of mainstream therapy in the near future until new technologies improve the process, oocyte cryopreservation may be an especially disappointing prospect for older women. With this in mind, this year PFC will take part in a large scale study involving Japanese IVF centers and other US centers on an alternative technology called vitrification. This involves an ultra-rapid freezing process that we hope will allow more oocytes to be frozen before they are compromised by the effects of the physical and chemical stresses indicative of typical slow freezing methods. Vitrification has shown good success with human oocytes and embryos in recent Japanese studies.

Categories

About the Blog

Welcome to the Pacific Fertility Center Blog! Nationally and internationally recognized for providing exceptional reproductive care, our team believes in empowering people with the knowledge they need to navigate their unique fertility journeys.

From information on the latest fertility treatments to valuable insights on egg donation, surrogacy, and everything in between, the Pacific Fertility Center Blog is your ultimate resource for all things reproductive care and support. Read on to learn more, and contact us today if you have any questions or want to schedule a new patient appointment.