Fibroids and their impact on conception

Patient Case

KJ was 35 year-old when she presented to PFC after attempting to conceive with her partner for over 2 years. They conceived spontaneously after 14 months, but the baby did not have a heartbeat at the first ultrasound. She subsequently had a miscarriage. Her cycles were regular at 28 day intervals with increasingly heavier flow over the last several months. Her workup included a cycle day 3 follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) of 10 mIU/mL, antral follicle count (AFC) of 8, and an anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) of 0.5 ng/mL. Hysterosalpingogram (HSG, dye test to evaluate the fallopian tubes) revealed open tubes on both sides and a large uterine cavity filling defect. Preovulatory transvaginal ultrasound showed a 8mm endometrial lining whose trilaminar pattern was obscured by a 25mm submucosal fibroid. Semen analysis was normal.

Discussion

Uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) are the most common pelvic tumors in women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a solid growth derived from muscular cells of the uterus. Fibroid cells are responsive to growth stimulation by estrogen and progesterone, and express these hormonal receptors. It is estimated that 30-40% of premenopausal women have fibroids in their uterus, with a higher prevalence in black than white women. Age of puberty and the number of pregnancies are also risk factors for the development of fibroids. Fibroids are slow growing tumors, averaging 1-2 cm every couple of years. A small percentage of fibroids will spontaneously regress. Most people with small fibroids are completely without symptoms. Those who do are bothered by heavy menstrual flow and pelvic pressure. Occasionally, fibroids can result in unpredictable bleeding patterns.

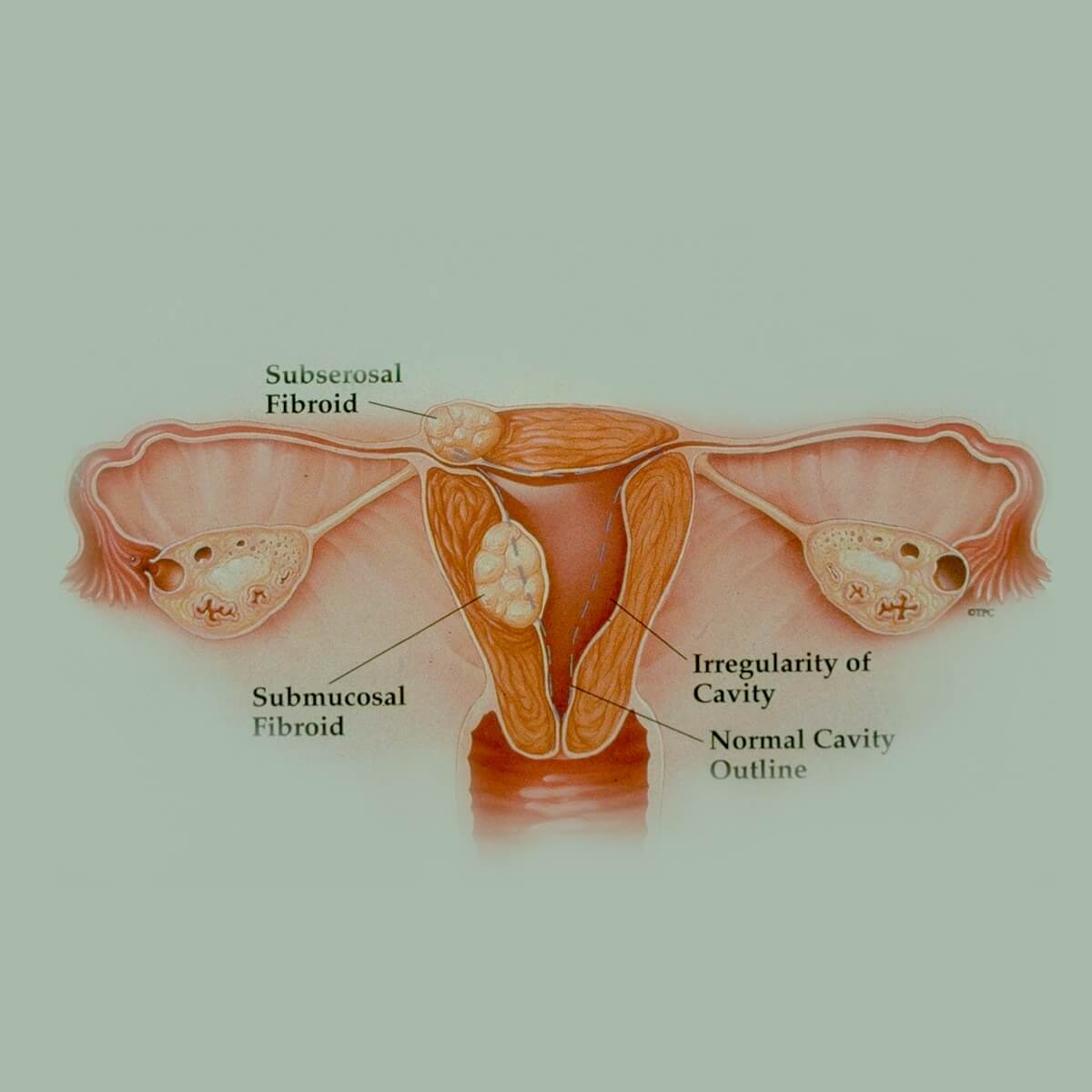

The relationship between fibroids and reproductive outcomes boils down to a key concept - location. The location of a fibroid is paramount in assessing whether it would adversely impact the ability to conceive. A fibroid that grows just underneath the lining of the uterine cavity (submucosal fibroid) may protrude into the cavity. If an embryo tries to implant in the endometrium overlying such a fibroid, it will encounter difficulty in properly establishing its vasculature to support a growing placenta and thus an ongoing pregnancy. This situation will lead to a failure to implant or ultimately an early miscarriage. Published studies on the effects of submucosal fibroids consistently show that the chances of pregnancy in women with submucosal fibroids are only 30-40% that of the chances in women who do not have fibroids. In addition, the risk of miscarriage is increased by 50-200% (Pritts 2009, Klatsky 2008). The clinical opinion by most physicians is that we should remove submucosal fibroids to improve the odds of conception in these women. Unfortunately, this is supported by only limited data from a few poorly conducted studies.

The effects of fibroids that are confined within the walls of the uterus (intramural fibroid) are still under debate. Multiple studies have reported inconsistent results on women with intramural fibroids who present for infertility treatment. Pooling these data together, a slight decrease (15-20%) in implantation rate and an approximately 30% increase in miscarriage rate are found in women with intramural fibroids compared to women who do not (Klatsky 2008). Similar results are shown in patients with or without intramural cavity non-distorting fibroids who undergo IVF (Sunkara 2010). In contrast, one study shows that egg donor recipients have equal changes of pregnancy with or without intramural fibroids that do not distort the uterine cavity, even when fibroids are larger than 4cm (Klatsky 2006). Furthermore, another analysis of pooled data from multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrates no improved odds of pregnancy in women with intramural fibroids who undergo surgical removal (Metwally 2012). When it comes to intramural fibroids, most clinicians based their recommendations partly on known evidence, which is limited, and partly on their overall assessment of how much the uterine environment is affected by the fibroids. The factors to consider are the total number of fibroids, their aggregate sizes in relation to the volume of the uterus, their proximity to the uterine cavity, and the extent of trauma and time it takes for recovery from a fibroid removal surgery. Risks and benefits must then be reviewed with the patient carefully.

Perhaps the best fibroids to have, if one must live with the presence of a fibroid at all, are those that grow from the outer surface of the uterus (subserosal). They do not appear to affect implantation and ongoing pregnancy regardless of size, with the exception that large fibroids may cause pain and discomfort as they grow in response to the hormonal milieu of pregnancy (Pritts 2009, Klatsky 2008).

Analysis of patient case

KJ presented with primary infertility and a history of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage. She also noted symptoms of heavy menstrual flow. Her evaluation revealed two underlying etiologies contributing to her infertility: diminished ovarian reserve and submucosal fibroid. Diminished ovarian reserve was evident by her elevated cycle day 3 FSH, low AFC, and low AMH. It may well be the primary reason why they had been unsuccessful in their attempts. It was also the dominant contributor to her prior pregnancy loss, which likely resulted from chromosomal abnormality within the embryo. However, she did have a substantially sized submucosal fibroid that was both symptomatic and distorted her uterine cavity on radiographic studies. Given the published evidence, it is possible that her submucosal fibroid provided the exacerbating factor that led to her miscarriage as well as her infertility. She would benefit the most from IVF. Despite the lack of Grade A evidence, it seemed clinically reasonable to recommend fibroid removal using a minimally invasive approach prior to IVF. KJ followed our recommendations and underwent a hysteroscopic (access of the uterine cavity by a camera through the cervix) resection of her submucosal fibroid followed by an IVF cycle. She is currently 39 weeks pregnant and anxiously expecting her son to arrive at any minute.

References:

- Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009 Apr;91(4):1215-23.

- Klatsky PC, Tran ND, Caughey AB, Fujimoto VY. Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;198(4):357-66.

- Sunkara SK, Khairy M, El-Toukhy T, Khalaf Y, Coomarasamy A. The effect of intramural fibroids without uterine cavity involvement on the outcome of IVF treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2010 Feb;25(2):418-29.

- Klatsky PC, Lane DE, Ryan IP, Fujimoto VY. The effect of fibroids without cavity involvement on ART outcomes independent of ovarian age. Hum Reprod. 2007 Feb;22(2):521-6. Erratum in: Hum Reprod. 2007 Apr;22(4):1195.

- Metwally M, Cheong YC, Horne AW. Surgical treatment of fibroids for subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14

— Liyun Li, M.D.

Categories

About the Blog

Welcome to the Pacific Fertility Center Blog! Nationally and internationally recognized for providing exceptional reproductive care, our team believes in empowering people with the knowledge they need to navigate their unique fertility journeys.

From information on the latest fertility treatments to valuable insights on egg donation, surrogacy, and everything in between, the Pacific Fertility Center Blog is your ultimate resource for all things reproductive care and support. Read on to learn more, and contact us today if you have any questions or want to schedule a new patient appointment.